Concerning J.R.R. Tolkien’s role in the continuation of this tradition, his Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún pulls from sources in The Poetic Edda and the Völsunga Saga; however, the difference with Tolkien’s version is that he takes all the source material and consolidates it into a more coherent story. Christopher Tolkien, the editor of Sigurd and Gudrún, dates his father’s poems to the early 1930s, guessing that it was taken up after he abandoned the Lay of Leithian near the end of 1931. Consequently, Tolkien sets off on the difficult task of taking this complex material; as Christopher Tolkien says, the “sources themselves, various in their nature, present obscurities, contradictions, and enigmas: and the existence of these problems underlay my father’s avowed purpose in writing the ‘New Lays’” (5). Although there is much that he keeps the same, Tolkien also has his own treatment of the curse of the treasure and its connection to the fate of Sigurd.

The concept of fate in The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún spells more meaning than the original story when it pertains to the culmination of events that began with the cursing of the treasure. Tolkien draws attention to this change at the very beginning of the lay in “Upphaf,” when the seeress, explaining to Odin what will happen at Ragnarök, says, “If in day of Doom / one deathless stands … then all shall not end” (63). This one person is the World’s Chosen, “the serpent-slayer, / seed of Ódin,” who is (or will be) Sigurd (Sigurd 63). Because Sigurd is of Odin’s seed, of the line of the Völsungs, Odin has a hand in the fate of the world by, first, engendering the Völsungs and, second, controlling what will happen in their lives so that he can take them to Valhalla, including Sigurd. Christopher Tolkien notes, quoting his father, “‘This motive of the special function of Sigurd is an invention of the present poet,’” which he also ties to his father’s Legendarium, as Túrin Turambar mirrors Sigurd in several ways (184). However, Andvari’s curse also plays a role as an instrument of fate, which Ódin puts to his advantage.

In “Andvara–Gull,” many of the same events occur as they do in Tolkien’s sources, with Loki striking Otr with a stone down by Andvari’s Falls and Hreidmar demanding a ransom from the gods for his son’s death. Loki catches Andvari in a net and orders him to give up his gold, which Andvari does, but because Loki would not allow Andvari to keep one ring, the dwarf pronounces, “‘My ring I will curse / with rue and woe!” which will be the “end untimely / of Ódin’s hope’” (Sigurd 69). Now, here specifically, Andvari uses the verb “curse,” as he is the agent of the illocutionary act, and his object of the curse is the ring, which is also tied to the rest of the gold.

J.L. Austin writes that, “[u]nless a certain effect is achieved, the illocutionary act will not have been happily, successfully performed,” which entails that “an effect must be achieved on the audience if the illocutionary act is to be carried out” (116). The audience here is Loki, and because he has heard and understood Andvari’s curse, he is able to pass it on to Hreidmar and the others. Therefore the curse is a successful illocutionary act, much the same as in The Poetic Edda. This just leaves the perlocutionary act, whose function is to initiate a set of consequences that culminate at a later date. For Loki, the perlocutionary act of the curse achieves a “perlocutionary object”, which could be to convince or persuade; however, in this case, the curse acts more as a warning and has the immediate result of Loki successfully being warned and relaying the message (Austin 118). However, Ódin has a different reaction to hearing the curse, saying,

“‘Whom Ódin chooseth

ends not untimely,

…………………..

it is to ages after

that Ódin looks’” (Sigurd 70-71).

Ódin is not deterred in the slightest. Knowing the fate of the world, he already has a plan to bring about his own designs by taking Sigurd to Valhalla, regardless of if the curse takes his life. Although the curse is the instrument of fate for Sigurd, Ódin also has a hand in the larger fate of the world.

Just as in Tolkien’s sources, Sigurd’s slaying of Fáfnir leads to the traditional asking of the slayer’s name which, again, Sigurd conceals and then reveals anyway. Still, Fáfnir warns him, “my guarded gold / gleams with evil, / bale it bringeth,” and “with fate of woe / this gold is glamoured” (Sigurd 110). Again, the curse is relayed to its ultimate victim, and so the illocutionary act of the warning allows for the continuation of the curse through the perlocutionary consequences. In Fáfnir saying that the gold was cursed, Sigurd is warned of the curse. But even so, in this interaction, although it is not mandatory, there is no “perlocutionary sequel,” which is that even though Sigurd is warned (the perlocutionary object), his immediate reaction (sequel) is not to be alarmed by the warning of the curse, which he just shrugs off (Austin 118).

Tolkien keeps many of the traditional aspects from his sources: in the revealing of Sigurd’s name, repetition of the curse to create suspense, the audience wondering how these events will come to pass; all of these “orally grounded considerations, then, help explain why the narrative function of prophecies and curses would exist to best serve the audience, whether listening to an oral tale or reading it in written form” (Sanders 9). It all boils down to the power of words as being acts and, as acts, they initiate consequences. The consequence for Sigurd as the inheritor of cursed treasure is that he is cursed by Brynhild as an oath-breaker, which sets in motion Gunnar and Hogni having their brother Gotthorm kill Sigurd in his bed. Subsequently, these traditions of Norse mythology and speech-act theory are then translated by Tolkien into his own mythology as he was thinking about them while writing The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún, in the curse of Mîm the dwarf and the consequences thereof.

Works Cited

Austin, J.L. How to Do Things with Words. edited by J.O. Urmson and Marina Sbisà, Harvard University Press, 1975.

Sanders, Elizabeth A. The Narrative Function of Prophecy and Curse in Medieval British Isle Epics. 2011. University of Arkansas, Ann Arbor, Master’s thesis, ProQuest.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Legend of Sigurd and Gudrún. edited by Christopher Tolkien, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2009.

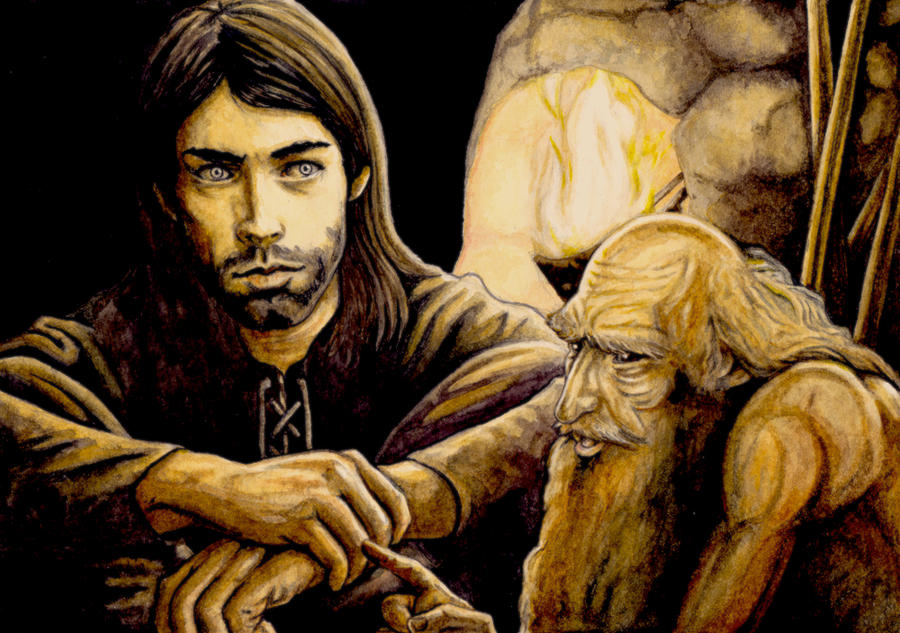

Header image: Siegfried Kills Fafnir, By Arthur Rackham (c. 1867–1939)