What started as a tale that Tolkien Invented for his children birthed The Hobbit, the prelude to The Lord of the Rings, and for the first time in his legendarium, dwarves and trolls collide. The Hobbit is also important because it seemingly reverses the meaning of “dwarf-natured” as being associated with avariciousness, like has been seen time and again of the dwarves in Tolkien’s mythology, particularly in “The Nauglafring.” By the time Tolkien is writing The Hobbit in 1930, he has already established an ambiguous origin for the Dwarves, found in his Quenta, written around the same time, and Tolkien has also indicated the Dwarves were not servants of Morgoth, so that they are not naturally evil. As now being a part of his legendarium, The Hobbit seems to show the Dwarves’ side of the story, as opposed to the Elves’ biases and half-truths, and their capability for heroics. They are no longer seen as just flies on the wall, sometimes buzzing in the faces of Elves and Men to stir up trouble.

Furthermore, the dwarves of The Hobbit are also rooted in the legendarium by association with one of the established races of Dwarves, the Indrafangs (Longbeards) of Belegost in the Blue Mountains, as Thorin says, “‘Durin! Durin! … ‘He was the father of the fathers of the eldest race of Dwarves, the Longbeards, and my first ancestor” (96). However, these dwarves are also rooted in Norse mythology, as all their names sans Balin’s can be found in the list of dwarf names in the Voluspa, plus their portrayal as being exclusively men as seen in previous iterations of the Dwarves’ history in the legendarium and elsewhere in Norse mythology.

As for the trolls, other than quick references found in Tolkien’s legendarium, they played no active part in the history of Middle-earth until their big debut in The Hobbit. While Tolkien is establishing his mythology for England, as previously stated, trolls would not have entered the collective imagination of the ancient English until the invading Vikings brought their mythology with them, so that they are not yet part of Morgoth’s brood. But the trolls of The Hobbit are very much like the trolls of Norse mythology. They are not good creatures and are often associated with giants, but they also have the unfortunate ability of turning to stone in daylight, which is what happens to the trolls William, Tom, and Bert in The Hobbit.

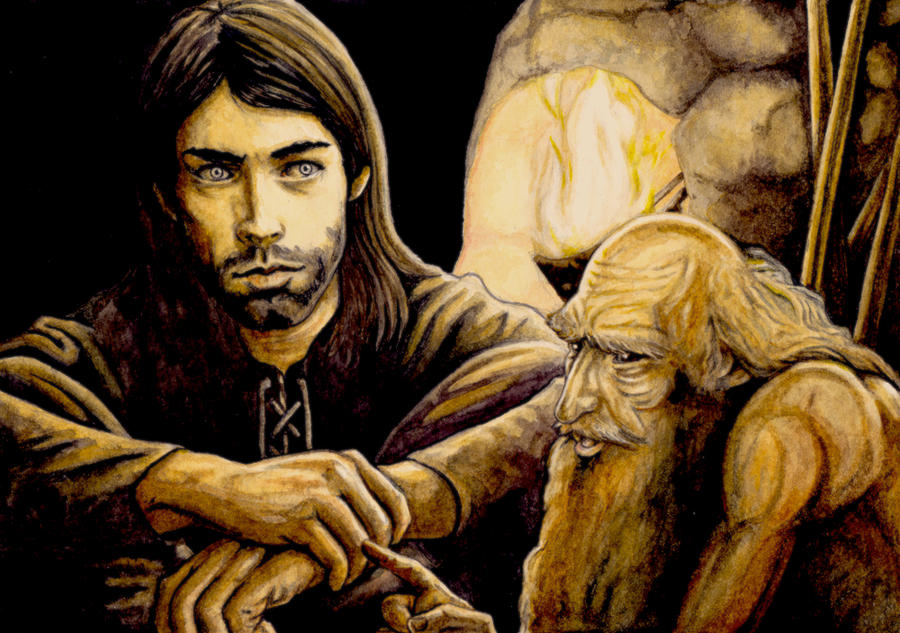

Gandalf’s plan of keeping the trolls bickering until dawn has resulted in them becoming statues, as the narrator says that “trolls, as you probably know, must be underground before dawn, or they go back to the stuff of the mountains they are made of” (Hobbit 80). This is reminiscent of The Poem of Helgi Hiorvardsson, where Atli’s flyting with the troll-woman Hrimgerd has kept her talking until daylight, saying, “as a harbour-mark you look hilarious, / standing there transformed into stone’” (Poetic 128). This seems quite an obvious source that Tolkien would have been aware of in The Poetic Edda, again, utilized as a direct borrowing, as he did not totally conceive of the notion of trolls turning into stone himself. But as John D. Rateliff notes in The History of The Hobbit, Tolkien “seems to have introduced the motif to English fiction,” indicating that this monstrous trait was not present in other stories involving trolls like “The Three Billy Goats Gruff” (102).

Instead of rooting himself in the present notion of what trolls are and their characteristics, Tolkien’s ingrained knowledge of Norse mythology comes to light to invest more in the sources of troll identity. Rateliff calls this “ignoring or sidestepping a modern fairy-tale tradition in favor of reviving an ancient folk-lore belief,” which is something Tolkien is known for elsewhere in his conception of the Elves (104). Another possibility of inspiration for Tolkien’s trolls, Douglas A. Anderson mentions that in 1926 Tolkien’s friend and colleague, Helen Buckhurst, read her paper “Icelandic Folklore” to the Viking Society for Northern Research, with the story “The Night Troll” highlighted, in which a troll turns to stone at dawn (80-82). Again, Tolkien’s legendarium has roots embedded in Norse mythology, and there are multiple sources in which he could have ingrained the idea of trolls turning into stone.

Returning to this notion of going back to “the stuff of the mountains they are made of,” there is now the sense that this is true of both trolls and dwarves. Tolkien had extensive knowledge of Norse mythology, so he surely must have also known All-Wise’s Sayings, when it dawns on the dwarf All-Wise that he must turn into stone. There was at least some belief that dwarves also had this ability, but Tolkien does not utilize this, of course, for his own Dwarves concerning sunlight. However, earlier in his legendarium he had given thought to the idea of the Dwarves coming out of the earth like the dwarves of Norse legend in The Book of Lost Tales, as the Nautar or Nauglath being one of the Úvanimor bred in the earth by Melko.

Then even after the writing of The Hobbit, when Tolkien develops the Dwarves as being the creation of Aulë, he uses the same language that he had for the trolls, “and they go back into the stone of the mountains of which they were made” (Lost Road 143). Although this is an unconfirmed belief by the Elves, it is an echoing of the origins of dwarves in Norse mythology and could even be a slight allusion to All-Wise himself turning into stone. This also hearkens back to the concept that “Dwarfs of the mountains are, like giants, liable to transform into stone, as indeed they have sprung out of stone” (Grimm 552). Of course, we know this not to be true of Tolkien’s Dwarves, as there is no instance of a dwarf turning into stone in sunlight or when they die, but it was an idea that floated around before Tolkien really fleshed out his Dwarves for The Hobbit.

However, this trait of turning into stone is a connecting tissue between trolls and dwarves and between Norse mythology and Tolkien’s. In his thesis, Aaron M. Brown develops the question of whether the monstrous trait of turning into stone was evil or the race bearing it, concluding that in “Tolkien’s mythology, dwarves and trolls are connected because he superimposes the above-mentioned trait from the mythic dwarf onto his new form of troll,” and because Tolkien has a change of heart with his own Dwarves, Brown suggests Tolkien “has made a creature of darkness a creature of light thereby entering them into the roster of good races who fight the elements, ideologies, and creatures of evil” (25-26). Both trolls and dwarves are first bred out of stone, as is later confirmed by The Silmarillion, but only dwarves become the creatures of light and made out of love by Aulë, while trolls become the mockery of Ents, shaped and made evil by Morgoth. Therefore, “dwarf-natured” has evolved into something that gives dwarves the ability to become heroes, first in The Hobbit, then in The Lord of the Rings.

Although Tolkien pulls from his expertise in Norse mythology to establish a background for his Dwarves and trolls, he is able to take the model and mold it himself into something that clearly has hints of the original soup of myth, but alter it in a way that adds its own unique flavor, and one that was mostly absent from the contemporary mind of Tolkien’s day. Thus, what Tolkien creates in his mythology becomes new to the public eye following the publication of The Hobbit, and especially after with The Lord of the Rings, and shaped so that forever after, the dwarves and trolls of Tolkien’s legendarium, although rooted in Norse mythology, are what we think of in our own mind’s eye in fantasy culture today.

Works Cited

Brown, Aaron M. Tolkien: Monsters, Midgard, and Medieval Origins. 2016. California State University Dominguez Hills, MA thesis, The California State University, https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/concern/theses/x633f1596.

Grimm, Jacob. Teutonic Mythology. Translated by James Stephen Stallybrass, 4th ed., vol. 2, London, 1883, Internet Archive,https://archive.org/details/teutonicmytholo02grim/mode/2up.

The Poetic Edda. Translated by Carolyne Larrington, Oxford University Press, 2014.

Rateliff, John D, and J.R.R. Tolkien. The History of the Hobbit. HarperCollinsPublishers, 2011.

Tolkien, J.R.R. The Lost Road and Other Writings, edited by Christopher Tolkien, Del Rey, 1996.

Tolkien, J.R.R, and Doulas A. Anderson. The Annotated Hobbit. Houghton Mifflin, 2002.